Definition of Personal Data

To know whether you should comply with the GDPR, the first question to answer is: do you process personal data? Personal data are any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. This video introduces the concept of personal data under the GDPR.

Per GDPR Art 4(1): ‘personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.

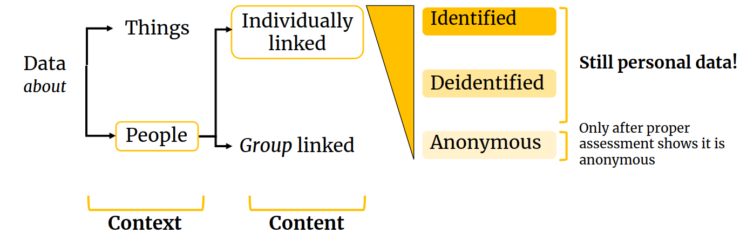

In practice, what makes data personal depends both on their context and content. The context indicates if data relate to individuals, and the content indicates if these individuals are “identified or identifiable”. When data refer to people as a group, and not as individuals, they are considered anonymous data. The transition from linked to a group to linked individually often follows a gradient: the more difficult it is to assign information individually, the less identifiable it becomes, and eventually it becomes anonymous.

-> Both identified and deidentified data should be considered as personal data. Only after a proper assessment has demonstrably proven that individual (re)identification is no longer possible, can personal data be confidently referred to as anonymous data – as even after removing names and other direct identifiers, there is often enough indirect information in deidentified datasets to enable individual reidentification.

For example, a date like 12 December 1973 is just a data point in the calendar – it is not personal data. A date of birth refers to people (group linked) – still not personal data. But someone’s date of birth is linked to an individual, it is someone’s personal data – as long as that individual is a real, living person. The GDPR does not cover deceased nor fictionalised individuals.

Likewise, an address like Princetonlaan 8a, 3584 CB Utrecht is the address of a building – as multiple people work there, by itself this address is not personal data. But “Dr. Janssen works at Princetonlaan 8a, 3584 CB Utrecht” can be personal data when there is only one Dr. Janssen working there – this information refers to one person only, and it is therefore personal data. Similarly, a last name or a date of birth are not personal data when the context is large enough, as many people will share the same last name, or the same date of birth within the context of a large group. But when the last name and date of are combined, they become quite useful in identifying people, even within a large group, and thus this combination would be personal data – as long as it is possible to identify single individuals within the group.

Another approach to determine if data is personal is to check if it is possible to single out individuals (I can see that a record refers to a single individual), to link data to other sources (I can see other datasets, like social media, to identify an individual), or to make a reasonable inference (I can confidently guess or estimate identity). This is the approach put forward by the EDPB, through its Opinion 05/2014 on Anonymization Techniques.

A lot of publicly available information is considered personal data. Obvious examples include posts in social media like Instagram or YouTube, but even a book, a report or a scientific research paper are personal data, as they are someone’s work – they are the personal data of their respective author(s).

In fact, the term any information in the GDPR definition above covers almost anything: The information can either be ‘objective’ such as unchangeable characteristics of a data subject as well as ‘subjective’ in the form of opinions, beliefs, preferences or assessments. It is also not necessary for the information to be true, proven or complete. This means that also mere likeliness, predictions or planning information is also covered by the GDPR. Even the name of a pet can be considered personal data, when it relates to a person – in that example, to the pet’s owner.

-> Always assume that any deidentified information collected or observed from people, like surveys responses, interview transcripts, observations notes, etc., is still personal data, until proven otherwise

Examples of processing of personal data:

Surveys usually collect datasets where the rows represent the responses of each individual and the columns the responses that each individual gave to each survey question. Even when no direct identifiers are requested, it is not difficult to see that in some cases the combination of survey responses will make some of the rows (and thus the individual behind this data) uniquely identifiable. But often, it is not possible to ensure if a survey dataset is going to be identifiable or not, until after data has been collected. That is why it is necessary to assume collected data is personal – until proven otherwise. The same argument holds for interview transcripts, as there is often enough information in the transcript text to render it potentially identifiable – again, assume it is personal until proven otherwise.

Even when the nature of the survey questions almost guarantees that collected data will be readily anonymous after collection, privacy and data protection laws still likely apply. For example, a researcher asking people on the street to state their preference from a list of 4 political candidates is collecting data that is definitely not personal, as the collected data would be just a tally of preferences not linked to anyone in particular. But stopping people on the street to ask them for their information is still an intrusion on people’s private sphere – even if it is one with a low impact – and as such, this intrusion would need to be justified.

Some datasets that are apparently not personal data are often indirectly linked to people. For example, a dataset with solar panel production data has several columns regarding power production data through time, including a column with solar panel geolocation data. As this geolocation can sometimes readily pinpoint the home address of the solar panel owner, the dataset should be considered personal data. A large enough reduction of geolocation accuracy may render it non-personal by making it unfeasible to link it to individual homes, but dropping the geolocation column altogether from the dataset would likely render it anonymous – as the rest of the data would no longer be (indirectly) linked or related to people.

The processing of freely and publicly available personal data, like social media data, contact information, basically any information with a personal name attached to it, like articles and other publications, is also covered by the GDPR – it is still necessary to demonstrate compliance of research projects that use freely available personal data. Failure to do so could even lead researchers to get a fine.

Publicly accessible personal data does not mean that those personal data also belong to the public domain. For example, information shared publicly by individuals on specific social media is usually shared in a certain context, and that context can be quite diverse – some information may even be shared by others specifically to violate someone’s privacy, such as doxing. Public availability of data should therefore not be mistaken for data intended to belong to the public domain.

The concept of pseudonymous data

“Pseudonymisation” of data means replacing any identifying characteristics of data with a pseudonym, or, in other words, a value which does not allow the data subject to be directly identified. Unlike anonymisation, pseudonymisation enables re-identification, as ‘additional information’ (like reidentification keys) is created and kept separate, that allows pseudonymisation to be reversible.

It is clear from the above definition that pseudonymous data remains personal data because it is still possible to (re)identify individuals using the reidentification keys. However, once these keys are deleted, pseudonymisation becomes irreversible – data is now deidentified. And as stated above, deidentified data becomes anonymous once it is not possible to single out individuals within, and it is not possible to link data to other sources or to make a reasonable inference to identify individuals within the data.

Pseudonymised/deidentified data is sometimes anonymous data when it is shared

As stated above, data becomes personal from its content and its context. If the context changes, it may be possible for pseudonymized data to become anonymous. For example, when pseudonymized data is shared with a party who are not able to reidentify the received data (either because they have no access to the reidentification keys, or because it is not feasible to them because it would require a disproportionate effort), then that data is in effect anonymous for that party – even if the same data is still personal data for the party that has the reidentification key.

In other words, the same set of pseudonymized data might be personal data for one party but not for another party, depending on the risk of reidentification. This “relative approach” to the definition of personal data has been recently confirmed (Sep 2025) by the CJEU’s judgment in the SRB case (Case C-413/23 P)